Summary

Takayasu arteritis (TAK) is characterized by granulomatitis that affects the large arteries, narrowing or occlusion of these arteries. This disease most often affects young women in the second and third decades of life. Although the exact cause of the disease is unknown, it is believed that genetic and environmental factors play a role in its occurrence.

Case Presentation

Medical history

A 42-year-old male patient presented to the clinic with complaints of postprandial abdominal pain and significant weight loss exceeding 30 kg over a three-month period. Additional symptoms included mild hypertension, decreased appetite, and generalized fatigue. The patient also reported intermittent claudication in the left lower extremity and weakness in the upper limbs.

Past medical history revealed a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease treated previously with Mesalazine, and a history of smoking for 15 years. The patient denied any alcohol use and had no notable

Past medical history revealed a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease treated previously with Mesalazine, and a history of smoking for 15 years. The patient denied any alcohol use and had no notable surgical, allergic, or genetic history. He had received all routine vaccinations, including the COVID-19 vaccine, three years prior.

Clinical examination:

On examination, the patient appeared fatigued and pale, with a temperature of 37.0°C and a pulse rate of 76 beats per minute in the upper right limb. Notably, there was an absence of pulse in the upper left limb. Blood pressure readings were 120/70 mm Hg in the upper right limb and 80/60 mm Hg in the upper left limb. Additional findings included an audible murmur over the abdominal aorta and the absence of pulses in the upper left and lower right limbs. Neurological examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

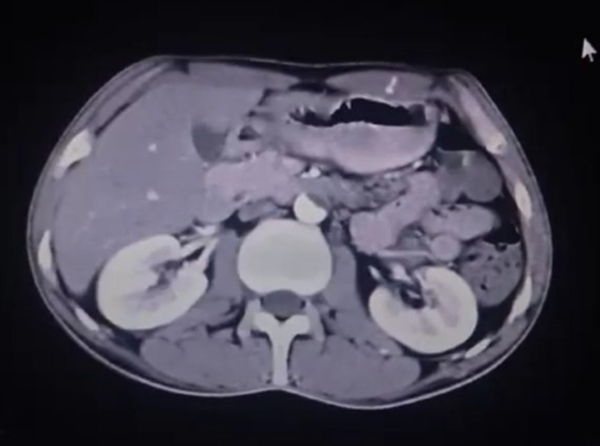

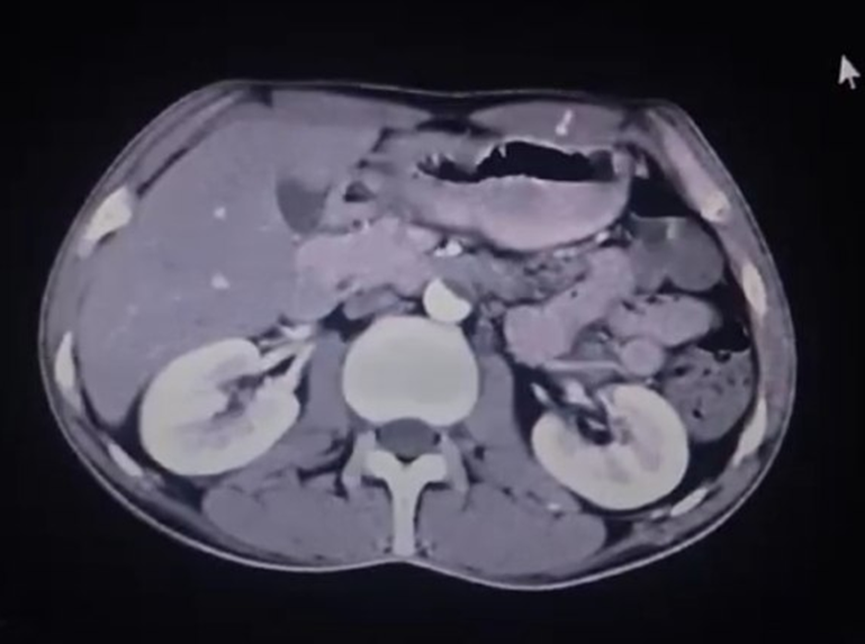

Laboratory analysis showed a high CRP of 10 mg/l and an increase in the sedimentation rate of ESR of 60 mm/h. Imaging studies, including CT scans, have revealed narrowing of the aorta and severe narrowing of several large arteries.

Diagnosis

The clinical findings and imaging results led to a diagnosis of Takayasu’s arteritis. The patient was started on high-dose prednisone (60 mg daily) and azathioprine (50 mg twice daily), with plans to titrate the doses gradually.

Follow-up

At 15-day follow-up, the patient reported an improvement in abdominal pain. Both abdominal pain and lameness improved significantly after 30 days.

Discussion

Takayasu’s arteritis is a chronic inflammatory condition that can cause severe complications if not accurately diagnosed and managed. The clinical symptoms are diverse, often resulting in delays in diagnosis. Thus, early detection and appropriate treatment are crucial to prevent complications like arterial dilatation and significant arterial narrowing.

Epidemiology

Takayasu’s arteritis is a rare chronic inflammatory disease that predominantly affects large arteries, particularly the aorta and its major branches. The epidemiology of Takayasu’s arteritis varies by region: the incidence is estimated at 1-2 cases per million in Japan and 2.2 cases per million in Kuwait[1]. In the Midwest region of the United States, the prevalence is approximately 8.4 cases per million population[2]. Takayasu’s arteritis primarily affects females, accounting for 80-90% of cases, and typically presents between the ages of 10 and 40[3].

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of vasculitis remains unclear, though genetic predisposition and immune mechanisms are thought to play a significant role. Histopathology typically reveals granulomatous inflammation with a predominance of cytotoxic T cells. Vasculitis is characterized by autoimmune inflammation, vascular remodeling, and endothelial dysfunction[3]. The disease progresses through three stages—active phase, chronic phase, and recovery phase—each presenting with distinct clinical features.

Clinical symptoms

Early symptoms of vasculitis are often nonspecific and may include fever, weight loss, fatigue, headache, tightness, joint pain, and night sweats. As the disease progresses, more specific vascular symptoms may develop, such as[4]:

- Claudication of the limbs

- Weak or absent pulse

- Blood pressure differences between limbs

- Murmurs over the affected arteries

- Hypertension (particularly with renal artery involvement)

- Aortic regurgitation

- Raynaud’s phenomenon

Additionally, neurological symptoms can arise, including headaches, vision disorders, stroke, and transient ischemic attacks.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosing coronary artery involvement in Takayasu’s arteritis (TA) can be challenging due to the nonspecific nature of clinical symptoms and the lack of specific diagnostic tests. However, various imaging methods are crucial in diagnosing TA, including:

- Angiography: Considered the gold standard for visualizing arterial injury and assessing the extent of the disease.

- Ultrasound and Doppler techniques: Used to assess arterial wall thickness and detect flow abnormalities.

- PET and MRI fusion imaging: Particularly useful for evaluating uncommon sites such as vertebral arteries.

Diagnostic criteria

The ACR-EULAR classification criteria for Takayasu Arteritis (TAK) include age at onset (less than 60 years) and evidence of large vessel inflammation. Additional points are assigned based on clinical symptoms and imaging findings, contributing to a comprehensive assessment of the disease.[5]

| Diagnostic criteria ACR-EULAR | |

| Absolute requirements | |

| Age ≤ 60 years at the time of diagnosis | |

| Evidence of vasculitis in imaging | |

| Clinical criteria | |

| Feminine gender | 1 |

| Chest diphtheria or coronal heart pain | 2 |

| Limp in the upper or lower extremities | |

| A murmur over one of the large subclavian arteries,aorta, carotid, renal,axillary,brachial, or iliac | 2 |

| Impulse of the arteries of the upper axillary, brachial, radial limb | 2 |

| Lack of pulse or absence or reluctance of the carotid artery | 2 |

| The difference in systolic pressure between the forearms is more than 20 mm g | 1 |

| Radiological standards | |

| Number of anatomical areas affected by stenosis , blockage, or aneurysm fixed by angiography or echo Choose only one | |

| Injury to one arterial area | 1 |

| Injury to two arterial areas | 2 |

| Infection of 3 or more arterial areas | 3 |

| Symmetrical injury to a pair of arteries fixed by carotid, subclavian or renal arteries | 1 |

| Abdominal aortic injury with injury to the mesenteric or renal arteries confirmed by imaging | 3 |

| Collect scores for ten items, if any. A score of ≥ 5 points is required to classify Takayasu’s arteritis. | |

Differential diagnosis

When evaluating Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK), it is important to consider several conditions that may present with similar symptoms. Differential diagnoses include:

- Subclavian Artery Steal Syndrome

- Infection-Related Vasculitis

- Malignant Disease

- Acute Mesenteric Artery Occlusion

- Polyarteritis Nodosa (PAN)

- Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA)

- Aortic Dissection

- Mesenteric Infarction

Management:

The management of Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK) requires a multidisciplinary approach. The primary goals of treatment are to reduce inflammation and prevent vascular damage.

Basic treatment typically involves high-dose corticosteroids, often starting at approximately 1 mg/kg daily. The dosage is gradually reduced as symptoms improve and inflammation subsides.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) form the cornerstone of medical therapy for TAK, helping to manage the disease and maintain long-term remission.

Immunosuppressants:

- Combination therapy: In cases where corticosteroids alone are insufficient, immunosuppressants such as azathioprine or methotrexate may be added to the treatment regimen. These drugs further suppress the immune response and help reduce reliance on corticosteroids.

- Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Inhibitors: For patients with Takayasu’s arteritis who do not respond adequately to corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, TNF inhibitors like infliximab and etanercept have shown promising results. These agents can be effective in managing Takayasu-resistant arteritis.

Biological agents

- Interleukin-6 inhibitors IL-6): IL-6 Receptor Antagonists: Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, has emerged as an effective treatment for Takayasu’s arteritis, particularly in cases of coronary artery stenosis. Tocilizumab has demonstrated the ability to induce healing in patients unresponsive to conventional treatments and has a steroid-sparing effect, allowing for reduced corticosteroid doses. Studies indicate that tocilizumab can lead to complete recovery in a significant proportion of patients.

- Janus Kinase Inhibitors: These newer agents are also being investigated for their potential in treating Takayasu’s arteritis, including coronary artery stenosis. Although their efficacy is still under research, they represent a promising area of treatment development [6]

Surgical interventions

In certain cases, surgical interventions may be required to manage complications such as severe vasoconstriction or blockage. These procedures can include:

- Angioplasty: A technique to restore blood flow by expanding narrowed or obstructed blood vessels.

- Bypass Surgery: A procedure to create an alternate route for blood flow around blocked or narrowed vessels.

These therapies are integral to managing the disease and improving long-term outcomes.

Complications

If left untreated, Takayasu’s arteritis can result in significant complications, including arterial vasodilation and severe narrowing of the arteries. These complications can lead to ischemia, high blood pressure, and potentially life-threatening events such as myocardial infarction or stroke.

Summary.

Takayasu’s arteritis should be considered in patients presenting with unexplained systemic and vascular symptoms. Early diagnosis and appropriate immunosuppressive therapy are crucial for improving patient outcomes and preventing severe complications.

Clarification:

This case was treated at Al-Quds Hospital, supported by Hand in Hand, by the resident doctor in internal medicine, Dr. Mustafa Armali, under the supervision of the supervising doctor Wassim Zakaria, Chairman of the Internal Diseases Specialization Council at the Syrian Board for Medical Specialization SBOMS.

References

[1] F. Onen and N. Akkoc, “Epidemiology of Takayasu arteritis,” 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2017.05.034.

[2] C. Sanchez-Alvarez, C. S. Crowson, M. J. Koster, and K. J. Warrington, “Prevalence of takayasu arteritis: A population-based study,” 2021. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.201463.

[3] S. Bhandari et al., “Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Takayasu Arteritis: A Review of Current Advances,” Cureus, 2023, doi: 10.7759/cureus.42667.

[4] D. Hrisrova and S. Marchev, “Takayasu Arteritis – A Systematic Review,” 2019. doi: 10.2478/amb-2019-0033.

[5] P. C. Grayson et al., “2022 American College of Rheumatology/EULAR classification criteria for Takayasu arteritis,” Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 81, no. 12, 2022, doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-223482.

[6] M. M. Peter A Merkel, “Treatment of Takayasu arteritis,” UptoDate. 2022. Accessed: Aug. 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-takayasu-arteritis